A significant part of my project, is how I execute the plan for creating a mindful situation. The research I have found discusses the physical act of mindfulness, in so far as learning how to focus and concentrate on immediate surroundings, using my senses to notice everything in real time, trying not to let my mind wander off into usual thought spaces. Whilst I have identified some key peer reviewed research which examines these themes, a significant part of my knowledge comes from my passion for reading nature writing. I listen to audiobooks & podcasts on the subject and also have paper books that I read and re-read. From the essayists (Jamie) to the adventurer / scientists (Macfarlane) and lifestyle writers, there is the common thread of an appreciation of the natural world and a slowness to their writing which indicates a deeper, more mindful understanding of our world. The photo above shows just a few that I have and which have contributed to my love of nature. I feel very fortunate to live in an area where there is an abundance of inspiration on my own doorstep. To understand my own subject, this immersion and commitment to my environment, must be practiced. Using quiet observation, contemplation and patience I have faith that I can create meaningful work.

Alyson Agar

I was pleased to find this very recent study, ‘Creating Wellbeing’ (Lemon, N et al, 2025) is a collection of essays which aims to show how creative practices “can revolutionise wellbeing and resilience in higher education, this groundbreaking collection brings together 25 academics who reveal how engaging with creative processes – from visual arts and crafts to performance and digital media – can serve as powerful tools for self-care and professional flourishing” (p1) within this is an essay by lecturer Alyson Agar, senior lecturer in Art and Design at The Northern School of Art. “Embodied Connections‘ (p75) is an essay derived from a study for her PHD. Alyson’s research explores the relationship between photography and film and the landscape, looking at how these activities can inspire connections to nature. This specific study is a result of her concerns, when during Covid-19 she considered how engaging with nature, through physical activity, e.g. nature walks, could have benefits to students and colleagues alike. She outlines her project here: “In 2024, I developed Embodied Connections Conversation Series: Women’s Conversations in Landscape and Climate through Collaborative Nature-based Photographic Practices, a year-long art-based research project based in Hartlepool, a coastal town in the northeast of England. The study consists of 12 walking and moving conversations with women and women-identifying artists, photographers and creative practitioners focused on creating participatory nature-based photographic imagery within the Hartlepool landscape” (p76) The key principle of the project was for groups of women artist participants to engage with the landscape as a group, walking through it in a sort of ‘tag team’ approach, as each person met up with the next, they would gift something from the natural environment, as a way to acknowledge the place and its ‘gifts’ this could be anything from a stone to a leaf, but this act likely instilled a sense of gratitude and appreciation for the place. Along the way participants would engage with their environment by creating art using natural materials (often anthotypes) in place. In her conclusion, Agar says “at the heart of the project is the formalised orbital structure, which encourages participation, reflection, and connection by creating nature-based photographic practice within the natural landscape as a mindful practice to improve wellbeing” (p85)

This study has been published at a perfect time for me. I have an ongoing interest in how women engage with the land and combined with creative practices, this seems to be a full circle event. It is an area of study or work that I would like to explore beyond university, as I strongly believe that mindfully engaging with landscape utilising creative practices, has significant potential in wellbeing.

Liz Wells – Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity

There are several examples given by Wells of the differences between a women’s approach to landscape photography and the approach from men. I have focussed on her chapter ”Women, Land and The Gaze’ (Wells, 2011: p185:203) She discusses how women tend to focus on relation between people and place rather than the land as vista. Also, rather than looking at the vast, sublime landscape, women have a tendency to explore more natural forms, looking closely and the scale of imaging would be more of a close up scrutiny, such as in botanical illustration. In other words, tending to look at the details. This is particularly relevant when I consider what I am drawn to in my own landscapes. I think about how I approach a shoot (I note here that the term shoot sounds too prescribed, I think it is more a walking, immersive experience that might provide an opportunity to take a photograph) and I consider whether the last 17 years as a parent has been the instigator of my foray into landscape photography. I think it probably has, although I focus a lot on history, I don’t know if I would have had the same instinctive response had I continued on a different path. Wells offers some explanation here, suggesting that women’s landscape photography is often ecological (a term she notes is unlikely to have been used 20 years ago, with climate having not been so central to landscape debates) although she asserts that this is most likely historically, socially, and culturally situated, rather than any biological trait; their work often foregrounds care, memory, connection and lived experience. It will be interesting to see how this changes over time, as men and women’s cultural experiences hopefully become less divided. Nowadays, there are more men taking on caregiving roles in Western society and I would like to see research on the impact of this in creative practices in the future. I personally believe that there are some biological influences, but I would rather avoid being too essentialist, instead considering that perhaps this would be too insignificant to make any obvious difference.

Wells writing links into the work of various nature writers that I have had an interest in for many years. I am drawn to the works of these writers, because of the richly detailed descriptions of their surroundings, the natural environments that they walk in and immerse themselves in. The evocative descriptions are phenomenological and akin to mindful practice in that they describe in great sensory detail. Although those listed here are women, I have also read essays by nature journalist Robert MacFarlane & Right to Roam activists like Guy Shrubshole.

Nan Shepherd

Arguably, the best known example of women’s nature writing in the UK is The Living Mountain, by Nan Shepherd (2014). Her ability to describe her surroundings in such infinite detail means the reader is transported to a seemingly magical place, with the promise of an overwhelming, sensory experience which I feel could pin you down. It is a short book but the joy for me in this, is that I can read and reread it when ever I feel I need a ‘Living Mountain tonic’ There are many paragraphs and quotes which I could show as examples that inspire me, one that comes to mind though is this one, because it is predominantly about using her hearing sense over sound and sight: In reference to the moving water on the mountain, she says “One hears it without listening as one breathes without thinking. But to a listening ear the sound disintegrates into many different notes – the slow slap of a loch, the high clear trill of a rivulet, the roar of spate. On one short stretch of burn the ear may distinguish a dozen different notes at once” (p26) Shepherds writing reiterates for me that understanding place means to have embodied attention and authentic lived experience. Her walking was the vehicle for a way of thinking and feeling, as she transforms the Cairngorms into a living, breathing thing.

Kathleen Jamie

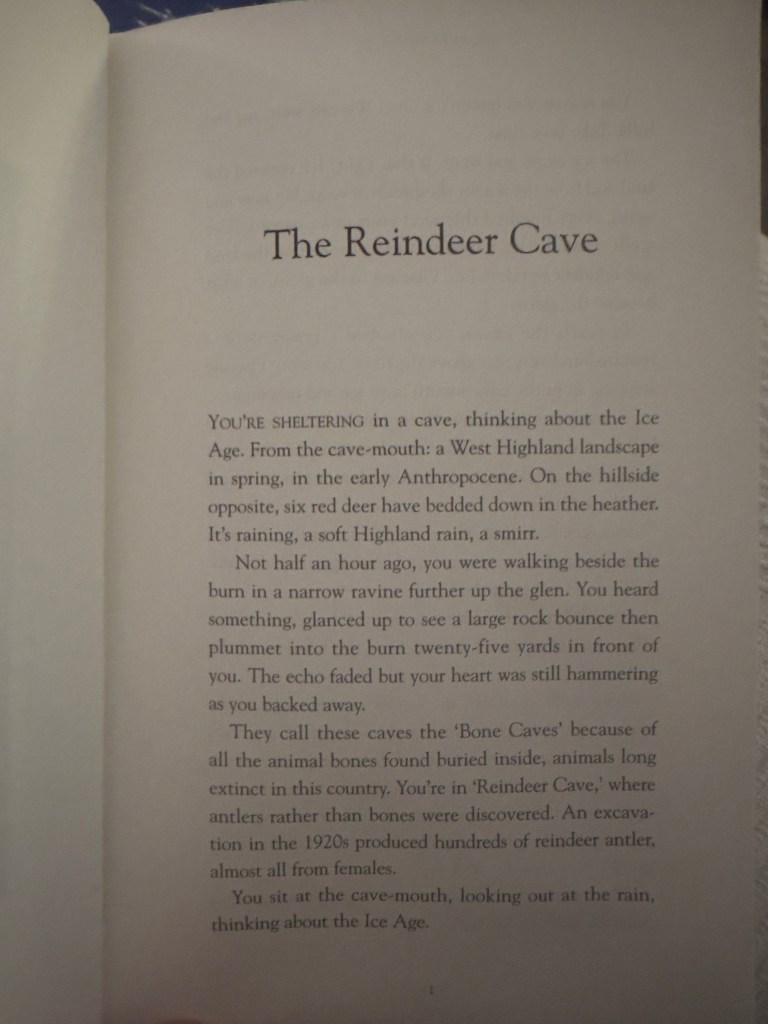

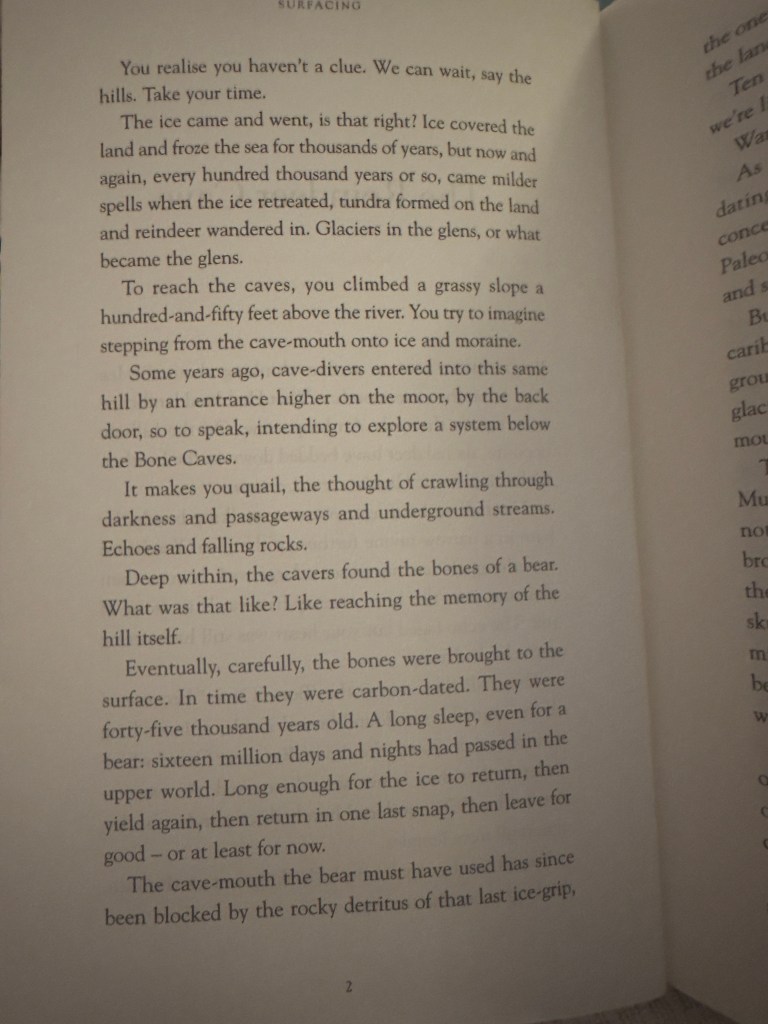

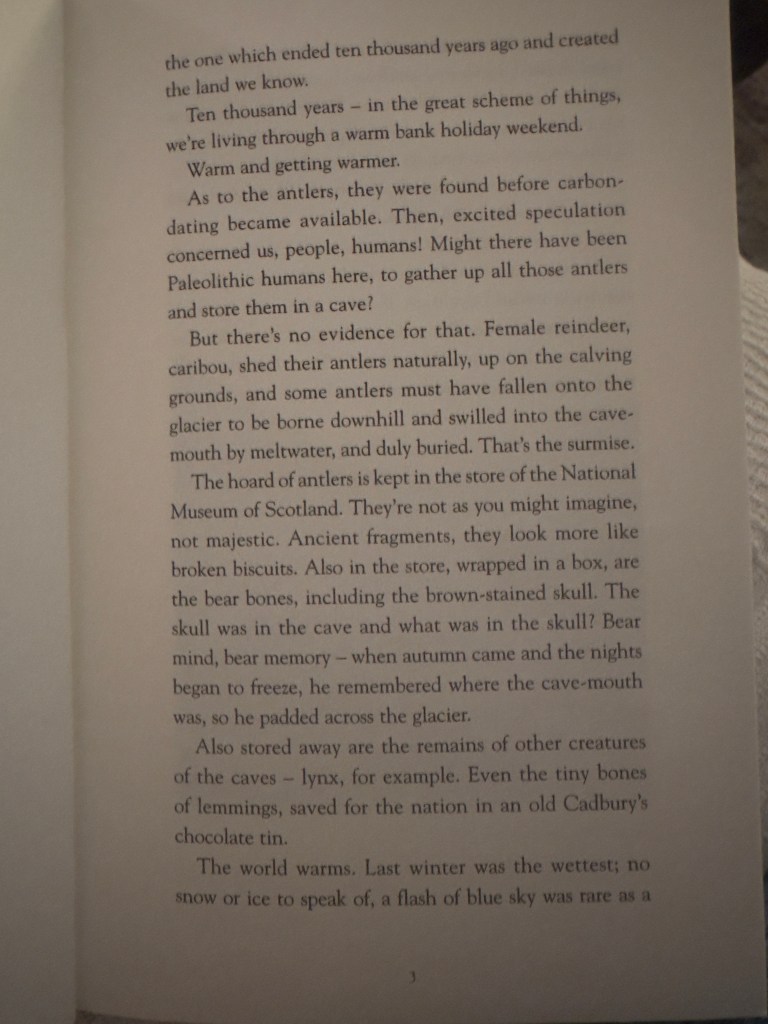

I have several books by Kathleen Jamie. I find her essays are perfect to calm a busy mind and as it intersects with phenomenology and topophilia, which I briefly discuss elsewhere, her writing has influenced my thinking around landscapes and attention to the environment. She addresses issues of place, culture and belonging as well as highlighting broader issues, relatying to land use and community. Her writing is almost like a sort of mindful recording. Landscape and nature are woven into human life as an embodied experience. and she reflects on the human experience. One of the most memorable essays for me was in her book ‘Surfacing’ (2022, p1) when she describes having walked up to sit at the mouth of a cave, the ‘bone caves’ so called because of the discovery of some 40,000 year old bones of a bear. She narrates as second person, the perceived view from the ‘cave mouth’ in the early Anthropocene, whilst foregrounding it against the Ice Age. Its an interesting way of perceiving the landscape and it carries the themes of temporality and dwelling, in a more lyrical narrative than the academic theory that I’ve read a lot of over the last few years. The text is below:

Kerri Andrews

Wanderers: A history of women walking (2020) is a brilliant collection of essays by Kerri Andrews. Spanning over 300 years, the essays are focussed on the following women: Elizabeth Carter, Dorothy Wordsworth, Ellen Weeton, Sarah Hoddart Hazlitt, Harriet Martineau, Virginia Woolf, Nan Shepherd, Cheryl Strayed and Linda Cracknell. Each chapter details the experiences and writings of these women as they’ve engaged with their chosen pass time, in different areas of the UK and abroad.

Dorothy Wordsworth walked a huge number of miles every day, from her cottage in Grasmere, which she shared with her brother William. She was orphaned at 12 after her mothers death and separated from her brothers as they were sent to boarding school and she was sent to live with relatives, never staying in any one place for too long. They were reunited as adults and had an incredibly close bond, especially after their brother Johns death. Although William is most well known for his writing, Dorothy’s diary’s and notes are full of incredible detail and are a arguably a tribute to the act of sensing ones surroundings. She would frequently walk huge distances, from dawn until dusk, as if unable to be still and at ease. As she retrod the same paths over and over, “memories began to accumulate along the way, lending new and powerful meaning to her favourite walks” (p62) Similarly, Linda Cracknell says “By virtue of walking a path that endures beyond the limits of human lifespans, we can inhabit the same space that our selves-that-were, and keep the path oepn for the selves-to-come” (p249) For Cracknell, the act of walking the same route over and over is to reconnect with a past version of herself, as well as to connect with those before her and to leave an impression as guide, for those of the future. She can see “a clear pathway between that 17 year old who was learning to draw and paint and the woman who writes in 2008” (p250). For Dorothy Wordsworth, these memories would prove to be hugely comforting, when after 30 plus years of walking her beloved Lake District, she developed a debilitating illness which prevented her from leaving home. For her, walking had been the stabilising factor in her emotional wellbeing, so when she also developed what we’d now assume was a dementia, it came as an extra blow. Although her short term memory was affected, the earlier events of her life persisted and so she could tap into her mind and recall the walks she had been on. This is one of the last poems she wrote (p84):

“No prisoner in this lonely room,

I saw the green Banks of the Wye,

Recalling thy Prophetic words,

Bard, Brother, Friend from infancy!

No need of motion, or of strength,

Or even the breathing air;

-I thought of Nature’s loveliest scenes;

And with memory I was there”

The idea of recalling memory and connecting through landscape reminds me of a walk I’ve made several times, from Ford near Temple Guiting, to Bourton on the Water. The route leads through several trails’ The Diamond Way, Windrush Way and Wardens Way. My grandmother used to walk daily along the section near Bourton from Lower Slaughter, when she was 14, to get to work. I always think of this when I am covering that particular section and sense her footsteps, realising how much of the same view we would be looking at. Andrews says that “for…women walkers, the pedestrian body becomes a conduit through which past, present and future are connected” (p251) which really does resonate for me. My reasons to walk and absorb myself in the landscapes I am most connected to are because I feel a great sense of comfort and reassurance there, I feel close to my ancestors and to my own childhood.

These are just a few examples of the inspirational women that have contributed to inform my practice, it is difficult to identify exact moments or passages in their writing as they’ve almost become part of some subconscious knowledge now but I know that collectively these works have seen my work change and become more meaningful as a result.